DOI: https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2025.19.01.12

Eduweb, 2025, enero-marzo, v.19, n.1. ISSN: 1856-7576

Cómo citar:

Babik, I., Viatokha, I., Sydorovych, O., Nevoenna, O., & Demydova, Y. (2025). Psychological and pedagogical strategies for the formation of emotional resilience in children. Revista Eduweb, 19(1), 181-195. https://doi.org/10.46502/issn.1856-7576/2025.19.01.12

Estrategias psicológicas y pedagógicas para la formación de la resiliencia emocional en los niños

Ivanna Babik

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1176-4933

PhD, Assistant, Department of Pediatrics No. 1, Faculty of Medicine No. 1, Lviv National Medical University named after Danylo Halytskyi, Lviv, Ukraine.

Iryna Viatokha

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-9006-9707

PhD, Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor of the Department of Pedagogy and Psychology, Ukrainian Institute of Arts and Sciences, Bucha, Kyiv region, Ukraine.

Olha Sydorovych

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4420-5748

Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of Special Education, Faculty of Pedagogical Education, Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Lviv, Ukraine.

Olena Nevoenna

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7578-9902

Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Associate Professor, Department of General Psychology, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

Yuliia Demydova

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6587-0152

Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences, Associate Professor, Vice-Rector for Scientific and Pedagogical Work and Youth Policy, Preschool Education Department, Faculty of Psychology and Pedagogy, Mariupol State University, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Recibido: 30/01/25

Aceptado: 22/03/25

Abstract

The study investigates the role of psychological and pedagogical strategies in generating emotional resilience in children. The basic focus of the research is on integrating SEL intervention, and the research deals with increasing issues of childhood emotional and psychological challenges promoted by social, academic, and global disruptions. The purpose of this research is to examine structured and culturally sensitive approaches that could develop emotional resilience and increase children's ability to compete with stress and adversity. With the help of experimental research design, the study is based on 150 children aged 8 to 12 years and divided into intervention and control groups. Data was collected through post-intervention assessments such as emotional resilience, skills, and behavioural observations. The result of the research showed that the intervention groups of children showed a significant improvement in emotional resilience indicators. Emotional regulations increased by 11.3%, and self-awareness increased by 16.1%, while social skills and adaptability also represented a significant improvement. These research-finding programs efficiently improve emotional resilience in children and provide essential skills to navigate adversity. The studies helped to develop a holistic approach to child development and focus on emotional well-being with the iconic success that required widespread adoption of SEL.

Keywords: emotional intelligence, psychological support, development of self-awareness, behavioural strategies, socio-emotional learning.

Resumen

El artículo analiza el impacto de estrategias psicológicas y pedagógicas en el desarrollo de la resiliencia emocional infantil. Se centra en programas de Aprendizaje Social y Emocional (SEL) para abordar los problemas emocionales y psicológicos en la infancia, exacerbados por perturbaciones sociales, académicas y globales. El objetivo es identificar enfoques estructurados y culturalmente sensibles que fortalezcan la resiliencia emocional y ayuden a los niños a manejar el estrés y la adversidad.

El estudio utiliza un diseño experimental con una muestra de 150 niños de 8 a 12 años, divididos en grupos de intervención y control. Los datos se obtuvieron mediante evaluaciones posteriores a la intervención, incluyendo mediciones de resiliencia emocional, habilidades sociales y observaciones conductuales.

Los resultados muestran que los niños del grupo de intervención presentaron mejoras significativas en resiliencia emocional. La regulación emocional aumentó un 11,3 %, la autoconciencia un 16,1 % y las habilidades sociales y de adaptabilidad también mejoraron. Estos hallazgos confirman la eficacia de los programas SEL para fortalecer la resiliencia emocional infantil y proporcionar herramientas esenciales para enfrentar adversidades. El enfoque holístico desarrollado promueve el bienestar emocional infantil y destaca la importancia de implementar ampliamente estos programas.

Palabras clave: inteligencia emocional, apoyo psicológico, desarrollo de la autoconciencia, estrategias conductuales, aprendizaje socioemocional.

Introduction

Research problem

Emotional resilience or emotional intelligence should be viewed as the child’s ability to withstand pressures in his or her life (Nieto-Carracedo et al., 2024).

That being said, over recent years, pediatric cases of anxiety and depression have increased drastically due to escalating social stresses, academic pressures, unstable families, and global disruptions, including the pandemic, for example, COVID-19 (Zafiropoulou & Psilou, 2024). These factors have led to the development of children who, with proper support, cannot cope with various ailments such as anxiety, depression, and behavioural difficulties. There are more serious outcomes related to neglect of childhood emotional trauma than simple psychological problems (Gumennykova et al., 2023). Academic and social capabilities may be poorly performed emotionally, which may cause emotional problems and hinder the whole development process. This is an issue of great concern because children who have poor emotional regulations can hardly be optimal in adulthood in all areas of life, including careers. Moreover, we see that these problems affect families, educators, and communities since they fail to mitigate this growing problem. We hear more about promoting children and encouraging individuals to have emotional strength, yet ironically, there is poor implementation of research-based practices to prevent high levels of emotions in children (Wyman et al., 2010; Osuji, 2012). Although many schools and families have initiated support-demanding systems, such support is frequently informal or random to the child’s development. Furthermore, cultural, economic and social differences increase the problem of inadequate interventions, primarily because all these resources are not available to all people. Mental health is affected at all stages of life, with stress and emotional challenges arising from transitions such as academic pressures in early adulthood, mid-life crises, and existential rumination in later years, highlighting the need for tailored mental health education and support systems (Chovhaniuk et al., 2023). Another cause of the multifaceted issue is technological development with a high growth rate. Inadequacy and stress can be augmented primarily by the usage of digital media and social networking in children’s lives as they are exposed to cyberbullying, unrealistic comparisons, and information overload (Reschly & Christenson, 2022; Davies & West, 2014). Diverse structures characterize modern families, shared parenting, evolving gender roles, and increasing multiculturalism, all of which contribute to emotional support and the socialization of family members. These dynamics highlight the need for educational programs aimed at helping families navigate ethical challenges and foster resilience in an era of rapid societal change (Tkachenko et al., 2023). These are the trends, on the one hand, while on the other, many traditional patterns of education and care do not reflect recent findings from developmental psychology and neuroscience that could help to overcome these difficulties. This research aims to meet this gap in the availability of structured, flexible, and culturally sensitive approaches to promoting resilience among children. Through the integration of knowledge derived from psychological theories, pedagogical principles and applications, the current study seeks to bridge the gap that exists within the theoretical and practical domains. In addition to improving individual happiness and satisfaction, such actions are necessary to raise a generation capable of overcoming adversity and creating a society that has much to offer.

Research Aim

This theory of the work consists of the research’s goal, which is to find, distinguish, and assess such strategies for psychological and pedagogical approaches to emotional vulnerability in children. Coping is a therapeutic characteristic that makes it easy for kids to experience stress, fight hardship, and succeed in different facets of life, such as learning and interpersonal interactions. This work aims to identify children's needs, considering developmental psychology, cognitive behavioural theories, educational practice, and goals. The other key aim is to offer concrete suggestions for educators, childcare providers and policymakers to apply resilience-promoting practices to current environments for children. The study insists on equity in implementing the specified methods, mainly catering to the needs of culturally diverse children. The work aims to teach children how to manage emotions correctly, helping them develop skills that are important for their future stable mental health and further socio-personal development while creating the corresponding conditions for proper society and community members.

Research Questions

Research focus

The current research work is focused on identifying and analysing general and educational psychological approaches towards building child emotional resilience. The inclusive definition of emotional resilience is the capacity of an individual to bounce back after a stressful event and manage stress. Critics of the field contend that emotional resilience simply means the phenomenon of coping. This remains significant, especially in childhood development, because it helps in the formation of what the individual will be for the rest of their life in terms of mental health and socialisation. Seeing that psychosocial, psychosocial resistance has emerged as a powerful contributory factor to human well-being, this research will, therefore, seek to inquire further into the process of psychosocial, psychosocial construction in line with organised approaches (Jindal-Snape & Miller, 2008). The theory base of this study comprises the principles derived from developmental psychology and cognitive behavioural paradigms. These theories give information on how children manage to comprehend and react to emotional inputs in a way that would prepare them for strategy implementation in conformity to the developmental age. For example, younger children will possibly require play-based interventions of emotional self-regulation, whilst older children may only understand and respond to reflective and problem-solving strategies. This differentiation ensures the strategies proposed here are not only good but also appropriate given the development of the students.

Moreover, the focus of this study is important for education and the concept of pedagogy, where emotional resilience is also an important factor. Children’s academic environments are a very important part of children’s lives; they spend most of their valuable time at school. Administrators, teachers, school counsellors, and other education professionals are in a good place to implement practices that foster resilience. Online psychological testing has emerged as an alternative format of psychological support, demonstrating its effectiveness in improving the psycho-emotional state of students and helping them overcome learning difficulties in times of socio-cultural turbulence’ (Reva & Demchenko, 2024).

The proposed aim of this research is to examine how behavioural techniques can be incorporated into commonly used teaching practices, including storytelling, goal-centred discussions and resilience-based games (Cefai & Cavioni, 2015). Also paramount to the attainment of the goal is broad strategies embracement. Children from varied cultural, socioeconomic, and familial backgrounds have feelings that should not be dismissed (Tillott et al., 2024). This study focuses on culturally appropriate practices to close these gaps so that the development of resilience can be possible for all children. For example, collectivist sample methods might involve communal and familial support, which might work better than mutual methods in individualistic cultural sample methods, which comprise self-scrutiny. In the last, the concerns of the study, therefore, shift to the home setting due to the important contributions parents and caregivers make (Fried & Chapman, 2012).

It is intended to offer useful guidance for parents on how to care for their kids’ emotions. By focusing on what psychological science has to offer, as well as best practices in education and culture, this research aims at defining an integrated approach to promoting children’s emotional well-being.

Research hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Psychological models that emphasize cognitive-behavioural approaches and social support systems are more effective in developing protective factors and fostering emotional resilience in children.

Hypothesis 2: Inclusive and culturally responsive pedagogical strategies significantly enhance emotional resilience in children across various developmental stages by addressing diverse social and cultural contexts.

Literature Review

Emotional resilience is a complex psycho-social resource that captures a person's ability to cope with and transform the stressors in his/her life (Konaszewski et al., 2021). When it comes to children, emotional stability is a very crucial factor as it defines their problem-solving skills, interpersonal relationships and achievements in their developmental tasks (Shamblin et al., 2016). In contrast to temperament, strength is described as a state factor in which an individual is exposed to varying practices from inside and outside, as in the external environment, including family, school, and community interplay. This dynamic nature places resilience in the limelight for intervention and development among children (Noble & McGrath, 2015). The roots of emotional resilience can be found in the theory of stress and adaptation, mapping out protective factors preventing negative consequences of adverse conditions. For example, while studying resilience, Rutter minor elements are a significant part like self-efficacy, self-regulation and, most importantly, having supportive and stable relationships in the child-building process. Such research findings have been incorporated into recent models, including DSM, Developmental Systems Theory, which underlines how molecular biology and environmental receptiveness in the early years of a child determine adaptation achievement capacity (Mota et al., 2016). The framework widely known in the discussion of resilience is Masten’s ‘Ordinary Magic, which states that resilience is a prosaic strength achieved through ordinary adaptive processes. Such systems embrace family adaptability, school climate, and community resources (Brunzell et al., 2019). In children, specific areas, including self-esteem, problem-solving skills, and the capacity to develop and maintain relationships with others, are critical in protecting resilience. For instance, a child who receives a carer’s emotional support is likely to develop effective strategies that help him or her deal with adverse conditions. The Ecological Systems Theory builds up the concept of resilience by studying how a child’s development is affected by transactions within the microsystems, mesosystems and macro-systems (Pace et al., 2022). These comprise the social-ecological context in which resilience does not simply occur for children but also others. For example, in a school valuing principle of inclusiveness and emotional safety, the essential prerequisite to resilience is met (Wosnitza et al., 2018). Cognitive theories also have implications for understanding emotional resilience, where it, among other postulations, posits that thinking processes determine emotional responses.

Self-efficacy emphasizes identifying that children with strong beliefs in their capability to cope with such difficulties are likely to persevere in the challenges (Brunzell et al., 2016). Also, the cognitive-behavioural theories focus on the issue of helping children learn how to change their negative thoughts, as well as improve their potential for dealing with stress and any other hardships constructively (Evans et al., 2024).

Defining the educational aspect of emotional resilience has gained much attention, especially concerning social-emotional learning (SEL) initiatives. Based on developmental and educational psychology, the above programs are meant to foster values like courtesy, self-control, and peaceful conflict-solving (Anderson & Dron, 2017). SEL is best supported by the theoretical framework of Vygotsky’s Social Constructivism Theory because the latter emphasizes the importance of interactions in the learning process (Miller-Lewis et al., 2013). Part-lesson arrangement of activities, reciprocal teaching and learning activities, and synchronous and interactive group discussions help build a context in which children can put into practice and promote resilience. Cultural aspects also determine a significant part of the so-called reserve in the face of stressors. Culture, as defined, plays a critical role, especially in dictating how children handle stressful events (Clausen et al., 2020; Waters & Loton, 2019). Collectivist cultures encourage interdependence and dependence on social networks so that the meaning of resilience may be anchored on these relationships. The concept of resilience for individuals of the individualist culture entails individualism by obtaining high personal accomplishment. It is for these reasons that it is important to employ strategies destined to be socioculturally sensitive in order to achieve the impact envisaged. Promoting emotional resilience in an educational context is a multi-faceted process where both what and how matter and where creating a context matters. The approach aims to create a classroom climate that promotes students’ individual and collective emotional safety and fostering, which, in turn, has the potential to promote success despite adversity (Khan et al., 2024). This section focuses on how the emotionally resilient education system can be implemented through curricular and classroom approaches as well as helpful school policies. SEL (social-emotional learning) is one of the important initial contending features for fostering resilience and is a foundation for improving learning outcomes. SEL deals with teaching students skills about emotions as well as skills to control feelings and values related to interpersonal relationships (Wang & Degol, 2016; Wang & Cheng, 2020). Integration of SEL into academic content enables educators to explain issues of emotional well-being and difficulties, hence offering students structural means to overcome emotions. For instance, long play sessions that involve organized interactive drama or group talking time allow the child to learn ways of managing their own emotional states and solve practical problems in structured play. The other generic teaching method that has proven effective in learning facilitation is student-centered learning, where emphasis is placed on participation, self-reliance and teamwork (Ungar et al., 2019). This, in turn, promotes student agency and self-efficacy- two key factors in resilience that are needed when managing academic challenges. Group work, assignments, and learning tasks that involve inquiries foster children to rise to challenges, to be calm and to develop patience (Lynch et al., 2004; McDonald, 2016). For example, teachers can organize tasks that involve feedback on achievements, ensuring students learn to understand that it is possible to learn from mistakes as opposed to failure. Programs of positive reinforcement and recognition are great examples due to the strong correlation between positive stimulus and personal resilience (Christenson et al., 2012). The message which teachers who embrace effort, persistence, and creative solutions give to their students is that the students are important and that their tenacity, as well as their creativity, is worthy of appreciation (Drew & Banerjee, 2019). Appreciation of individual /group performance leads to positive thinking that helps the students perceive the challenge as a normal part of learning. Specific acts that one can implement include complimenting on specific actions taken, promoting peer acknowledgement, and setting incentives to considerably enhance the work of strength-promoting. Other useful lessons that can be included in the school program are mindfulness and stress-coping skills. Activities such as deep breathing exercises, guided meditation, and reflection help students develop tools to avoid stress (Lereya et al., 2016).

They also not only promote concentration and control of feelings but also enable students to do appropriate things when faced with adversity. In addition to this, teachers can also continually conduct mini sessions before or after the lessons, after a break or before the break in the classroom, making it a normal routine for the students (Tillott et al., 2024). Teacher-student relationships are one of the most essential parts of social/emotional learning. Instructors who can listen and show empathy for students’ challenges are able to help students find support (Drane et al., 2021). When students understand their teachers as caring and concerned with their lives, these students are more likely to look for instructions and help when they are in trouble. This trust creates a safe emotional climate and makes the student comfortable to risk, voice various concerns, or solve emerging problems (Schonert-Reichl et al., 2012). Emotional expressions in texts strongly depend on the sociocultural context, communication goals, and the relationship between communicators, emphasizing the importance of context in understanding emotional states. Real-life problems and the application of problem-solvers enhance the continuity of the topics, which builds protection for the students by allowing them to solve the problems themselves. For example, trainers can set up problem-based assignments where they recreate concrete business scenarios, and students physically discuss the possible means of a contingency (Finkelstein et al., 2005). By subjecting them to different variables or learning formats, these exercises help teach flexibility, problem-solving, and persistence. Furthermore, resilience is supported by the corrective role of peer mentoring programs. Grouping should be done in a way that students get to share experiences with other students or older students with strategies to cope with their destinies (Gullotta et al., 2003). Not only does it allow mentees to gain great insights and ideas, but it also allows mentors to construct leadership and empathy features. Schools can develop the idea of the mentoring concept as part of the co-curricular activities so that students can be supported to support other students. The more the teachers will come to know about the mental state of their students. On the other hand, the incorporation of students and cultural contexts into classroom teaching and learning practices enhances the feeling of belonging to that classroom. By adopting culturally sensitive curricula, the resilience framing created by teachers is likely to be more meaningful to the students’ real-world experiences. This helps to prevent any child from feeling ignored or left out so that they can get support from within themselves, drawing on past experience (Mota & Matos, 2015).

Lastly, schools need to work towards having systematic interventions within resilience frameworks that include formulation and implementation policies fostering emotional health for students. Programs like shared hatred, coping with stress, and educating teachers on how to raise emotionally intelligent children are essential to a coherent platform. In this way, the teachers' preparation for understanding and controlling students’ emotions guarantees that all the school members are afforded a proper setting regarding their emotions (Matson, 2017). Consequently, promoting emotional resilience at educational institutions is a complex process requiring both intentional educational activities and emotional support as well as supportive rules and regulations. The values of care, respect, and voice are the three caring principles that can enable students to gain resilience in their emotional aspect to be ready for challenges in current society. Such a systematic approach helps the students to achieve academic goals while at the same time helping the child cope with life challenges with ease. Cultural and environmental factors play a significant role in determining the level of emotional resilience a child acquires. The cultural imperatives and norms predispose the emotions expressed, interpreted and regulated. For instance, the collectivist culture promotes communal support and dependency, offering a sound social support system that enhances resilience (Leontopoulou, 2006).

On the other hand, individualist societies focus more on the independent responsibility of the child. Other external factors, such as socio-economic status, the safety of the environment, and resource availability, also influence childhood. Positive context, referring to securely attached relationships, safety, education and healthcare, also affects people’s emotional self-resourcefulness. On the other hand, risk factors such as poverty, violence or instability can hinder resilience if other factors, such as guardian or neighbourhood-supported programs. Similarly, schools and the community setting form other primary contexts where resilience can be grown (LaBelle, 2019). Culturally sensitive solutions make children feel wanted in society, reducing emotional issues such as low self-esteem. Culturally competent solutions give children a sense of acceptance and belonging within their society. Whenever children impute into their environment familiar patterns of identity, conventionalism and valuable systems or beliefs belonging to them, they develop good morale (Byrko et al., 2022). This also helps minimize feelings of rejection or isolation, which may lead to emotional problems such as low self-esteem. Through such inclusion, the children feel safe overcoming hurdles that challenge their emotional capacity and general mental health (Kim, 2015). This is how many hurdles faced due to social or cultural aspects are better dealt with remarkably, and the relevant strategies are proposed (O’Connor et al., 2017). Culturally and professionally, therefore, patterned causal factors form a contextual network, which either enhances or constrains a child’s ability to cope and go through an ordeal in her environment (Martínez & Acosta, 2017).

Methodology

General Background

This research is focused on acknowledging and assessing psychological and pedagogical approaches to foster children’s emotional literacy. Coping with stress with positive emotions and remaining stable throughout the process is receiving growing attention as an important form of resource). This study aims to examine the interventions underpinned by social and emotional learning (SEL) with an emphasis on emotional competencies, behavioural methods, and self-awareness. The evaluation of interventions to promote the resilience of children takes place according to an experiment design. Ethical considerations were upheld to the highest level: anonymous consent, anonymization of data and voluntary participation, among others. For instance, consent forms pass information concerning the study and activities, and a participant’s parent or guardian and the school administration put their signature on it. Data was kept safe, and any information that could directly identify a participant was deleted in order to adhere to institutional as well as international protocols regarding research on children.

Sample

The study was administered to 150 children aged 8 – 12 in primary schools in the selected districts. The sample size was estimated via a power analysis to achieve 80% power to compare a sample of clinical levels of resilience for the identified groups. In this case, stratified random sampling was used in soliciting participants; this helped in considering the gender, socioeconomic status, and previous academic performance as requested by the objective of the study, hence the need to determine other experiences of building resilience. Participants were divided into three groups. It therefore created an Intervention Group A, an Intervention Group B and a Control Group. In the IG-A, participants underwent a rigorous SEL program for 12 weeks that entailed weekly 1-hour workshops to enhance the spread of emotional understanding, self-control, and social skills. Some of the activities included simulation, discursive activities, and breathing exercises. The traditional lesson and ordinary class work were taught to Intervention Group B, in which none of the components of SEL lessons were incorporated. Conversely, the control group maintained a standard school curriculum without mediation during the experiment. The inclusion criteria included the following: the participant must be in a primary school class, be able to speak the main language of the research study used in the study and have parental consent. Those children diagnosed with psychological or developmental disorders or those with previous experience in SEL-based interventions were excluded for purity of comparison. The SEL workshops conducted for Group A were directed to enhancing emotional regulation while participating in activities based on developmentally appropriate practice. For example, enacting roles for negotiation allowed the development of concern with others, the use of acceptable ways of handling disagreements, and the practice of staying focused and calm during stressful events. These sessions were very engaging and differed according to the age of the targeted group. The traditional practice of Group B meant daily lessons with student demonstrations of show-and-tell values and sample academic items that explicitly excluded aspects of SEL. This division underscored how practical SEL approaches are compared to business as usual in the classroom. The formation of the groups and interventions mentioned above offered this research the necessary data for understanding the particulars of the psychological and pedagogical climate most beneficial to the growth of the child’s emotional strength.

Instrument and Procedures

Various research instruments have been used, which are explained below. According to the Emotional Resilience Scale for Children ERSC, the study was altered to assess the cognitive, emotional, and social resilience reliability levels to prove Cronbach’s alpha value to be 0.85. For the case of the Behavioural Observation Checklist BOC, the underlying instrument is applied to measure behavioural response towards stress, along with the social behaviour during classroom learning, While for the agenda of parental feedback forms. These tools are used to gain some understanding of the subject’s emotional and behavioural changes in children observed at home. A Baseline Assessment is done in week one to achieve pre-intervention levels of emotion resilience by administering ERSC. It is also employed to gather behavioural data and parents’ responses. The intervention Phase is more than eight weeks in its foundation, and in Group A, twice a week. SEL workshops include practices, constructions, and skill practices. Group B provides a basic curriculum ahead of any additional augmentation, and the last group consists of conventional class assignments without specific targeted intervention. The post-intervention assessment is better done in week eight, utilizing the same instrument to determine shifts in emotional stability and behavioural functioning. All sessions were conducted with the help of teachers and psychologists who know SEL more than mentors for sessions. The interventions are correctly developed and comply with the educational norms, and the interventions are ensured to fit in the school setting.

Data Analysis

The collected data was analyzed using quantitative and qualitative methods to ensure comprehensive analysis and provide effective interventions. In the quantitative analysis, descriptive and inferential statistics are used, and in the descriptive statistics, baseline and post-intervention ERSC scores are summarised for all groups. In Inferential statistics, the tests were paired to compare pre-and post-intervention scores in each group. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test differences between intervention and control groups. The effect sizes were calculated to ensure the magnitude of the intervention impact. The qualitative analysis is based on automatic analysis of parental feedback and observations that help understand behavioural and emotional changes. Nvivo software was used to decode themes and understand improvements in empathy, self-regulation, and peer interactions. Moreover, inter-rater reliability for BOC positive was conducted with the help of two independent observers' score behaviours and triangulation findings from ERS that enhance the validity of the research. The ERSC was selected out of the measure of resilience as it captured broad cognitive, affective, and social-mental health resilience, and the study was interested in improving the overall resilience in children. This makes the instrument highly reliable, and the internal consistency coefficient was very high. The Behavioral Observation Checklist (BOC) records actual behaviour and describes it in the context of emotional and social situations; thus, it can be used as an effective intervention measurement tool. The statements to parents were chosen to get a holistic view of parents on changes in children’s behaviour beyond school. These are well established in educational and psychological research, hence this study's internal reliability and constructoflidity.

Results and Discussion

In this research section, there is a comprehensive discussion about the findings from experimental research that focus on generating emotional resilience in children using psychological and pedagogical strategies. The results align with the research objectives that provide innovative insight into the impact of structured SEL interventions (Table 1).

Quantitative Results

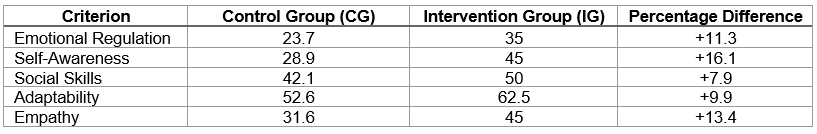

Table 1.

The Comparison of Emotional Resilience Score across Groups

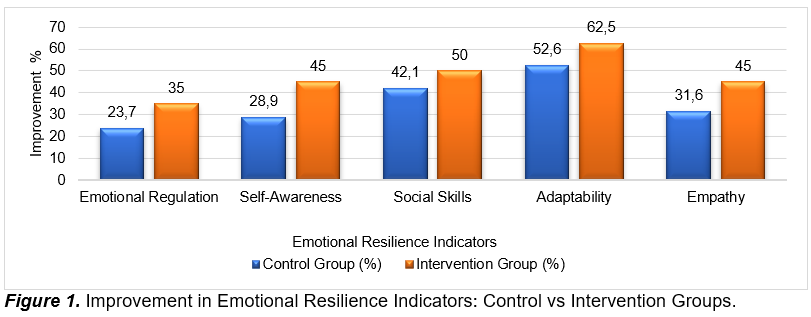

The graphical representation is about the improvement of key emotional resilience indicators between the control and the intervention groups (Figure 1).

The observations from quantitative data represent that there is a significant improvement in improving emotional regulations as the intervention group participants demonstrated an 11.3% improvement that was increased over the control group (Meng et al., 2023). It also shows improvement in empathy and social skills, and the score increased by 13.4% and social skills by 7.9%. The improvement across all the criteria is achieved with a valid SEL framework, and its efficiency generates emotional resilience (Meng et al., 2023).

Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative data is derived from parental feedback and classroom observation that represented substantial behavioural changes among children in the intervention group. Children had better control over desires during peer interactions, which represented a few conflicts. The participants actively engaged in group tasks that generated an inclusive and empathetic environment. The journals of children reflected deeper information about their emotional states, and the findings represented parental feedback about home behaviour.

Innovations in research

The inclusion of multi-model tools such as mindfulness practices and guiding discussions is helpful to ensure a well-rounded approach. The integration assessment techniques are based on a combination of quantitative metrics with qualitative feedback that provides a deeper understanding of resilience development (Tillott et al., 2024). The integration of feedback collected from parents helps the researcher to capture behavioural changes beyond the academic environment.

Conceptual Application

The research confirms the efficacy of SEL strategies in improving resilience, specifically in designing curriculums. It represented that structured SEL could seamlessly integrate into the existing school curriculum; the teacher training highlighted the need for skilful educators and implementation as techniques, while policy implications are helpful for developing policies as a core component of the primary education system. The results are summarised as the research continuously supporting the hypothesis that structured SEL intervention could significantly improve emotional resilience in children. The experimental progress of groups across multiple indicators focuses on the requirement for schools to prefer social-emotional learning frameworks that are significant components of education. A comparison of findings in the existing research studies highlighted that different aspects of research highlight similarities and differences that provide a clear understanding of the significance of the findings (Marheni et al., 2024). The interpretation of the result demonstrated that structured intervention efficiently improves emotional resilience among children. The findings showed that the intervention groups participated in activities that resulted in a much higher improvement in emotional resilience compared to the control group, which had no specific intervention. The intervention group represented an improvement in emotional resilience components, including emotional regulation, self-awareness, social skills, adaptability, and empathy. The emotional regulation score in the intervention group increased by 11.3%, which is higher than the increase in the control group.

The SEL interventions included different techniques, such as mindfulness and emotional awareness exercises, that help manage the emotions of children (Li, 2023). The previous research studies demonstrated greater support for the idea that SEL programs have a positive impact on the emotional regulation of children. Moreover, self-awareness is closely related to emotional intelligence, which was increased by 16.1% in the intervention group. Research studies emphasize the role of self-awareness in improving emotional resilience.

In the context of social skills, the intervention group represented a 7.9% improvement, representing SEL activities focusing on interpersonal communication and cooperation in improving the ability of children to interact with others in an appropriate way. Such improvement is supported by the research conducted by Zins et al. (2007), which represents that SEL interventions generate positive peer relationships and improve communication skills. The research shows a significant increase in the intervention group related to adaptability as there was a 9.9% improvement in adaptability, which is significant for emotional resilience and helps children to navigate changes and adversity (Marheni et al., 2024). The literature highlighted the significance of adaptability as a basic component of emotional intelligence and interventions that focus on the success of helping children adapt to challenging situations. Additionally, empathy is also another key component of emotional resilience that was increased by 13.4% in the intervention group. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, has foundations for emotional resilience, and generates compassion and cooperation. Research has continuously shown that SEL programs could improve empathy in children, resulting in improvement in overall emotional and social development (Marheni et al., 2024). The findings of the research consistently show that there are similar research studies on SEL interventions. As Zins et al. (2007) explored, SEL programs significantly increase emotional intelligence among students, which is directly connected to emotional resilience. The current research study demonstrated that SEL interventions could generate skills related to emotional regulation, self-awareness, and empathy that contribute to better emotional and social outcomes. Moreover, Campbell et al. (2016) represented the intervention targeting emotional competencies such as self-awareness and emotional regulations that resulted in improved emotional resilience among children (Ivankov et al., 2023; Willis & Nagel, 2015). Emotional intelligence and academic self-concept were found to significantly contribute to students' achievements in mathematics, highlighting the importance of integrating social and emotional development into academic curricula (Akaneme & Metu, 2024). Comparatively, in the research, Campbell et al. (2016) implemented a wide range of emotional competencies tools, such as parent reports and teacher observations, that validated and improved resilience. On the other hand, the current research combined behavioural observations and parental feedback that added a layer of insights into the effect of SEL interventions in different contexts. Another notable difference is identified as compared to other research studies that the scale and intensity of intervention.

Campbell et al. (2016) used an extended intervention period of 6 to 12 months; however, the current research is based on eight weeks and still represents a substantial improvement that suggests a shorter and more concentrated SEL program that could significantly impact emotional resilience. However, it is significant to note that the length of the intervention could be impactful on the changes observed and intervention code improved results (Tillott et al., 2024; Havryliuk & Balashov, 2024; Suldo et al., 2008; Ungar et al., 2019). Generally, current research findings supported the broader literature on SEL and emotional resilience; however, there are different areas where the research results are slightly different. For example, improving social skills was not considered an improvement in emotional regulation and empathy. SEL interventions are recommended to improve interpersonal interactions, peer influences, and exposure to social skills training, which plays a significant role in developing these skills. The research conducted by Li (2023), Wosnitza et al. (2018) recommended that factors beyond the classroom, such as family dynamics and relationships, could impact the development of social competencies. Another significant area related to the impact of SEL on academic performance focuses on the research. It addresses the other research studies that show that programs positively impact academic performance due to improved emotional regulation and stress management. The current study examines study outcomes and explores how emotional resilience is improved by SEL and its impact on academic success.

Study Limitations

The results of the research are promising, but several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size of 150 respondents, such as children, is adequate statistically, but it restricts the generalisability of research and the impact of interventions in different cultural, social, and academic contexts. Research could be conducted by considering a larger and more diverse sample size that examined the generalisability of research findings in different populations. Secondly, the research is dependent on a relatively short intervention period of eight weeks, and the duration is sufficient to observe significant improvement in emotional resilience. Research is required to analyze sustainability and its impact. The research follow-up assessment in different months after the interview provided valuable insights about the lasting impact of SEL intervention. Moreover, dependence on parental feedback is one of the basic qualitative sources that may increase bias. Although efforts were made to mitigate the errors, future studies could generate benefits by integrating more objective behaviour and reports that contribute to valid research findings. The result of the research provided strong evidence that SEL intervention could significantly increase emotional resilience among children. The intervention group represented significant improvements in emotional regulation, self-awareness, social skills, and empathy that support the effectiveness of structured SEL programs to promote these key components of resilience. The research contributes to increasing literature on SEL that represents the positive impact of the targeted intervention on the emotional resilience of children. There is a need for further research to explore the long-term impact of the SEL program and identify the role of external factors in increasing the broader applicability of this intervention in different groups. The research is based on the significance of incorporating SEL into the educational curriculum as a source of emotional resilience in children. By developing such skills, we could use the tools that are required for the challenges, which will result in healthier and more adaptive behaviours and improve overall well-being.

Conclusions

This study is based on a critical analysis of generating emotional resilience among children, specifically while facing social and academic requirements and social challenges. The research ensured that structured interventions could significantly improve the key components of emotion resilience, including emotional regulation, self-awareness, empathy, and social skills. The research findings reinforce the value of the SEL program and highlight the significant requirement for their integration into the educational system to educate children with significant tools for navigating the adversities in life. The research results focused on providing children with the psychological and pedagogical support necessary to develop resilience and ensure they can face challenges and maintain confidence. The highlighted research questions represented that psychological theories and pedagogical strategies are also designed to fulfil the developmental needs and cultural aspects in which children are involved. The research helps develop an inclusive and culturally sensitive approach to emotional resilience. It ensures that children from different backgrounds can attain objectives from an appropriate intervention to generate unique experiences. The indication of research findings is broader as schools, policy-makers, and educators must work collaboratively to implement resilience programs beyond academic achievements and focus on emotional well-being. Educators must be trained to identify emotional challenges and develop a supportive environment; however, parents and guardians should actively participate in emotional development programs for children. Overall, the research develops paradigm changes in the mental health approach of children and the resilience to promote a holistic view of development that prepares children to thrive socially and emotionally changes. Integrating SEL into everyday educational practices helps create directions for future generations to overcome life's challenges and promote resilience and emotional strength.

Bibliographic references

Akaneme, I. N., & Metu, C. A. (2024). Predicting Mathematics Achievement: The Role of Emotional Intelligence and the Academic Self-Concept. Futurity of Social Sciences, 2(3), 64-77. https://doi.org/10.57125/FS.2024.09.20.04

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2017). Integrating learning management and social networking systems. Italian Journal of Educational Technology, 25(3), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.17471/2499-4324/950

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed positive education: Using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(1), 63-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., & Waters, L. (2019). Shifting teacher practice in trauma-affected classrooms: Practice pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. School Mental Health, 11(3), 600-614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8

Byrko, N., Tolchieva, H., Babiak, O., Zamsha, A., Fedorenko, O., & Adamiuk, N. (2022). Training of teachers for the implementation of universal design in educational activities. AD ALTA: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 12(Special Issue 02-XXVIII), 117-125.

Campbell, S. B., Denham, S. A., Howarth, G. Z., Jones, S. M., Whittaker, J. V., Williford, A. P., … & Darling-Churchill, K. (2016). Commentary on the review of measures of early childhood social and emotional development: Conceptualization, critique, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 19-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.01.008

Cefai, C., & Cavioni, V. (2015). Beyond PISA: Schools as contexts for the promotion of children’s mental health and well-being. Contemporary School Psychology, 19(4), 233-242. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40688-015-0065-7

Chovhaniuk, O., Bashkirova, L., Meleha, K., & Yakymenko, V. (2023). Study of the state of health in the conditions of constant numerous transitional and intermediate stages. Futurity Medicine, 2(2), 26-34. https://doi.org/10.57125/FEM.2023.06.30.03

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., & Wylie, C. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

Clausen, J. M., Bunte, B., & Robertson, E. T. (2020). Professional development to improve communication and reduce the homework gap in grades 7-12 during COVID-19 transition to remote learning. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 443-451.

Davies, R. S., & West, R. E. (2014). Technology Integration in Schools. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 841–853). New York, NY: Springer New York.

Drane, C. F., Vernon, L., & O’Shea, S. (2021). Vulnerable learners in the age of COVID-19: A scoping review. Australian Educational Researcher, 48(4), 585-604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00409-5

Drew, H., & Banerjee, R. (2019). Supporting the education and well-being of children who are looked-after: what is the role of the virtual school? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(1), 101-121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0374-0

Evans, L., Singer, L., Zahra, D., Agbeja, I., & Moyes, S. M. (2024). Optimizing group work strategies in virtual dissection. Anatomical Sciences Education, 17(6), 1323-1335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2473

Finkelstein, N., Rechberger, E., Russell, L. A., VanDeMark, N. R., Noether, C. D., O’Keefe, M., … & Rael, M. (2005). Building resilience in children of mothers who have co-occurring disorders and histories of violence: intervention model and implementation issues. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 32(2), 141-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02287263

Fried, L., & Chapman, E. (2012). An investigation into the capacity of student motivation and emotion regulation strategies to predict engagement and resilience in the middle school classroom. Australian Educational Researcher, 39(3), 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-011-0049-1

Gullotta, T. P., Bloom, M., Kotch, J., Blakely, C., Bond, L., Adams, G., … & Ramos, J. (Eds.). (2003). Encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion. Boston, MA: Springer US.

Gumennykova, T., Pryimak, V., Myroshnychenko, N., & Bazyl, O. (2023). Analysis of Trends in Pedagogy and Psychology: Implementation of Globalization Solutions. Futurity Education, 3(2), 55-78. https://doi.org/10.57125/FED.2023.06.25.04

Havryliuk, D., & Balashov, E. (Eds.). (2024). Training of specialists in the field of psychological and pedagogical education of children through the prism of adaptation to emergencies: Resilience approach: The materials of the international round table (Ostroh town, February 15–17, 2024). Ostroh: Publishing House of the National University of Ostroh Academy. https://resiliencev4.oa.edu.ua/assets/files/materials_of_the_international_round_table_february_2024.pdf

Ivankov, V., Chukhlib, A., Stender, S., Azarenkov, G., & Nazarenko, I. (2023). Análisis de las perspectivas de introducción de las tecnologías digitales en la economía y la contabilidad ucranianas. REICE Revista Electrónica de Investigación En Ciencias Económicas, 11(22), 68-86. https://doi.org/10.5377/reice.v11i22.17343

Jindal-Snape, D., & Miller, D. J. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educational Psychology Review, 20(3), 217-236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9074-7

Khan, M. A., Kurbonova, O., Abdullaev, D., Radie, A. H., & Basim, N. (2024). Is AI-assisted assessment liable to evaluate young learners? Parents support, teacher support, immunity, and resilience are in focus in testing vocabulary learning. Language Testing in Asia, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-024-00324-x

Kim, H. (2015). Community and art: Creative education fostering resilience through art. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(2), 193-201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-015-9371-z

Konaszewski, K., Niesiobędzka, M., & Surzykiewicz, J. (2021). Resilience and mental health among juveniles: role of strategies for coping with stress. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01701-3

LaBelle, B. (2019). Positive outcomes of a social-emotional learning program to promote student resiliency and address mental health. Contemporary School Psychology, 27, 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00263-y

Leontopoulou, S. (2006). Resilience of Greek youth at an educational transition point: The role of locus of control and coping strategies as resources. Social Indicators Research, 76(1), 95-126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4858-3

Lereya, S. T., Humphrey, N., Patalay, P., Wolpert, M., Böhnke, J. R., Macdougall, A., & Deighton, J. (2016). The student resilience survey: psychometric validation and associations with mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0132-5

Li, S. (2023). The effect of teacher self-efficacy, teacher resilience, and emotion regulation on teacher burnout: a mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185079. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1185079

Lynch, K. B., Geller, S. R., & Schmidt, M. G. (2004). Multi-Year Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Resilience-Based Prevention Program for Young Children. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 24(3), 335-353. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPP.0000018052.12488.d1

Marheni, E., Afrizal, S., Purnomo, E., Jermaina, N., & Cahyani, F. I. (2024). Integrating emotional intelligence and mental education in sports to improve personal resilience of adolescents. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, (51), 649-656. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9142090

Martínez, E., & Acosta, A. (2017). Los Derechos de la Naturaleza como puerta de entrada a otro mundo posible. Revista Direito e Práxis, 8(4), 2927-2961. https://doi.org/10.1590/2179-8966/2017/31220

Matson, J. L. (2017). Handbook of social behavior and skills in children. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64592-6

McDonald, C. V. (2016). Evaluating junior secondary science textbook usage in Australian schools. Research in Science Education, 46(4), 481-509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-015-9468-8

Meng, Q., Yan, Z., Abbas, J., Shankar, A., & Subramanian, M. (2023). Human–computer interaction and digital literacy promote educational learning in pre-school children: Mediating role of psychological resilience for kids’ mental well-being and school readiness. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2248432

Miller-Lewis, L. R., Searle, A. K., Sawyer, M. G., Baghurst, P. A., & Hedley, D. (2013). Resource factors for mental health resilience in early childhood: An analysis with multiple methodologies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-7-6

Mota, C. P., & Matos, P. M. (2015). Adolescents in institutional care: Significant adults, resilience and well-being. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(2), 209-224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9278-6

Mota, C. P., Costa, M., & Matos, P. M. (2016). Resilience and deviant behavior among institutionalized adolescents: The relationship with significant adults. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal: C & A, 33(4), 313-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-015-0429-x

Nieto-Carracedo, A., Gómez-Iñiguez, C., Tamayo, L. A., & Igartua, J.-J. (2024). Emotional intelligence and academic achievement relationship: Emotional well-being, motivation, and learning strategies as mediating factors. Psicologí a Educativa, 30(2), 67-74. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2024a7

Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2015). PROSPER: A new framework for positive education. Psychology of Well-Being, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-015-0030-2

O'Connor, M., Sanson, A. V., Toumbourou, J. W., Norrish, J., & Olsson, C. A. (2017). Does positive mental health in adolescence longitudinally predict healthy transitions in young adulthood? Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 18(1), 177-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9723-3

Osuji, U.S.A. (2012). The Use of e-Assessments in the Nigerian Higher Education System. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 13(4), 140-152. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/113711/

Pace, U., D’Urso, G., Zappulla, C., Di Maggio, R., Aznar, M. A., Vilageliu, O. S., & Muscarà, M. (2022). Ethnic prejudice, resilience, and perception of inclusion of immigrant pupils among Italian and Catalan teachers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(1), 220-227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02098-9

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2022). Handbook of research on Student Engagement. Cham: Springer.

Reva, M., & Demchenko, Y. (2024). The Role of Online Psychological Testing in a Learning Process: The Ukrainian Case. E-Learning Innovations Journal, 2(1), 23-40. https://doi.org/10.57125/ELIJ.2024.03.25.02

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Smith, V., Zaidman-Zait, A., & Hertzman, C. (2012). Promoting children’s prosocial behaviors in school: Impact of the “roots of empathy” program on the social and emotional competence of school-aged children. School Mental Health, 4(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-011-9064-7

Shamblin, S., Graham, D., & Bianco, J. A. (2016). Creating trauma-informed schools for rural Appalachia: The partnerships program for enhancing resiliency, confidence and workforce development in early childhood education. School Mental Health, 8(1), 189-200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9181-4

Suldo, S. M., Shaunessy, E., & Hardesty, R. (2008). Relationships among stress, coping, and mental health in high‐achieving high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 45(4), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20300

Tillott, S., de Jong, G., & Hurley, D. (2024). Self-regulation through storytelling: A demonstration study detailing the educational book Game On for resilience building in early school children. Journal of Moral Education, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2024.2403992

Tkachenko, L., Gumennykova, T., Pletenytska, L., & Kholokh, O. (2023). Transforming the role of modern family: Ethical Challenges. Futurity Philosophy, 2(3), 17-38. https://doi.org/10.57125/FP.2023.09.30.02

Ungar, M., Connelly, G., Liebenberg, L., & Theron, L. (2019). How schools enhance the development of young people’s resilience. Social Indicators Research, 145(2), 615-627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1728-8

Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315-352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9319-1

Wang, X., & Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest, 158(1S), S65-S71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

Waters, L., & Loton, D. (2019). SEARCH: A meta-framework and review of the field of positive education. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 4(1–2), 1-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-019-00017-4

Willis, A. S., & Nagel, M. C. (2015). The role that teachers play in overcoming the effects of stress and trauma on children’s social psychological development: evidence from Northern Uganda. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 18(1), 37-54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9282-6

Wosnitza, M., Peixoto, F., Beltman, S., & Mansfield, C. F. (Eds.). (2018). Resilience in education: Concepts, contexts and connections (1st ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Wyman, P. A., Cross, W., Hendricks Brown, C., Yu, Q., Tu, X., & Eberly, S. (2010). Intervention to strengthen emotional self-regulation in children with emerging mental health problems: proximal impact on school behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(5), 707-720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9398-x

Zafiropoulou, M., & Psilou, A. (2024). Building mental resilience in children: The role of teachers and the whole-school setting. In Advances in Early Childhood and K-12 Education (pp. 211–242). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-8312-4.ch008

Zins, J. E., Bloodworth, M. R., Weissberg, R. P., & Walberg, H. J. (2007). The scientific base linking social and emotional learning to school success. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation: The Official Journal of the Association for Educational and Psychological Consultants, 17(2–3), 191-210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410701413145

Este artículo está bajo la licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0). Se permite la reproducción, distribución y comunicación pública de la obra, así como la creación de obras derivadas, siempre que se cite la fuente original.